On Thursday, September 18, 2014, I set out on my first solo offshore adventure in attempt to qualify for next year's Bermuda 1-2 Yacht Race--a 1,300 mile race comprising a single-handed leg from Newport, RI to Bermuda, and a double-handed leg back to Newport. The qualification requirement for Mini sailors, as specified in the Notice of Race (NOR) is sailing 200 miles offshore for no less than 48 hours--all other eligible boats have a qualification requirement of 100 miles / 24 hours. I sailed offshore technically for 29 hours before heading home, and clocked in nearly 205 offshore miles--most in between 17 and 28 knots of breeze, and while bashing through tall, steep, short-period waves that, more often than not, would break over the deck of my diminutive 21-foot Mini Transat boat.

Although I did not technically qualify as I was not offshore for 48 hours, my adventure was by no means a failure. As some have reminded me, I went FAR outside my comfort zone, returned home safely (and with no breakages to report), and with an additional 205 miles of well-earned and hard-fought ocean sailing experience--nearly 176 of which were achieved in 24 hours.

Before I try to describe the journey in some detail, let me first thank everybody who tracked me online, and offered amazingly reassuring and positive feedback as I sent some alarmingly negative sat comm messages when conditions became toughest. Although I did not receive your comments while underway, I looked at each message when I got back, which helped get my psyche back to equilibrium. Thanks especially to former colleague on the bow, Guy Rittger, for putting things into perspective. I'm no Webb Chiles, but yes, even after getting bounced around in a washing machine for the better part of the trip, and suffering from a bit of seasickness as a result, I finished with a Code 5 asym and full main, and surfed my way home between major shipping lanes in 20 knots of wind speed and upwards of 12-13 knots of boat speed. I could have gone faster with the full genoa and Code 2, and a better trimmed main. But, as my good friend Peter Beardsley reminded me before I left Larchmont, I didn't need to be a hero out there.

Here's how things went down. Scroll to the bottom if you just want the synopsis.

PREPARATION.

Back in August, I made the decision to tackle my first solo offshore some time in September, when the breeze was stronger and more consistent, air temperatures were not too cold, and when water temperatures were still relatively mild at around 70 degrees Fahrenheit. At the end of August, I began watching weather systems developing in the North Atlantic, including daily analysis of isobar charts and forecasts from PredictWind. I also used PredictWind's weather routing tool to find a course that would allow me to reach as much as possible over the required 200 miles. All models predicted a weak low-pressure system moving across the east coast near the waters south of NY Harbor on Thursday, September 18 through Sunday, September 21. This system would bring northwest winds to start, which would then clock (move clockwise, i.e., to the right) to the east and then to the south as the system moved past. I made the decision to head out into the ocean in connection with this system, which I determined would provide me with my desired reaching conditions. What I didn't anticipate was how much this breeze would kick up the sea state on the continental shelf that makes up the New York Bight.

At the same time I was analyzing weather, I prepped the safety gear, food, water, and layers I would need for two days offshore. My principal safety gear consisted of my Spinlock Deckvest and 2-clip / cow hitch safety line, which allowed me to clip into any number of hard points on the boat as well as my jack lines. In addition, I had a safety package provided by the safety experts at Landfall Navigation that included:

- Winslow 4-man ultra-light life raft, which weighs in at 32 lbs.

- ACR GlobalFix iPRO 406 MHz GPS EPIRB, mounted to the mast.

- ACR ResQLink GPS personal locator beacon, mounted to my Spinlock Deckvest.

- Offshore flare kit

With food, I tried to keep weight to a minimum, but pack enough to keep my energy up. Other than the homemade turkey and roast beef subs made by my ever-so-understanding wife, I loaded the boat with Hershey's dark chocolates, Clif Bars, Clif Shot Bloks, Starbucks Via coffee, Twinings Earl Grey tea, and some dehydrated meals from REI--Mountain House breakfast skillet, AlpineAire pepper beef and mesquite BBQ chicken, and MaryJanesFarm Outrageous Outback Oatmeal. With water, I brought 4 gallons assuming I would consume 1 gallon of water per day and built in a buffer just in case.

Selection of layers was made easy, thanks to a kit supplied by Helly Hansen. Offshore foulies were obviously a must. I brought with me my Helly Hansen Aegir ocean jacket and pants. HH's new line of ocean sailing gear was developed with Team SCA--the same Team SCA competing in the upcoming Volvo Ocean Race. So I had no doubt the Aegir gear would work well for me 100 miles offshore in the North Atlantic. But, as you read below, these pieces only work if you actually wear them! In terms of base layers, I brought with me a pair of HH Warm pants, my HH Warm Freeze 1/2 Zip top, and a backup top. For mid-layers, I had my HH Crew Vest, H2 Flow Jacket, and slightly heavier HH Crew Midlayer Jacket.

Other essential items included gloves, a fleece beanie, merino wool socks, and ocean boots. If you want to know more about how my co-skipper, Sam, and I dress, check out our "How to Dress a Sailor" video, here.

DELIVERY FROM LARCHMONT TO NEW YORK HARBOR.

I keep Abilyn at Larchmont Yacht Club in the Western Long Island Sound during the season. There are two ways to get to the ocean from here--80 miles east out of Long Island Sound, or 40 miles west and south down the East River and out of NY Harbor. I opted for the shorter route, which required that I fastidiously honor the currents in the East River, which can get as high as 4 knots. According to AyeTides, my handy iOS app, the current at Hell Gate would be slack at 0638 EDT on Thursday morning. Given that my outboard has a short shaft, it wouldn't be able to handle the standing waves that develop in Hell Gate at max current. Yes, shaft size does matter. So I decided to hit Hell Gate at slack before ebb based on advice from fellow Mini sailor, Josh Owen.

Given this time frame, I departed Larchmont at 0230 EDT and arrived at Hell Gate--14 nm away--about 20 minutes ahead of schedule, which gave me a slightly foul current, but nothing unmanageable. Once past midtown, I was motor-sailing at speedy 7-knot clip all the way past the Brooklyn Bridge and the Battery as the ebb tide produced an increasingly favorable current.

If you haven't already done it, I highly recommend transiting the East River at sunrise. The city is absolutely beautiful.

I arrived at Liberty Landing Marina across New York Harbor in Jersey City at 0830 EDT, where I was able to regroup, rig up some additional lines and my passive radar reflector, and get a couple hours of shut-eye before continuing on to the ocean.

OCEAN BOUND.

At 1300 EDT on Thursday afternoon, I hoisted the main and pulled off the slip. Although the breeze hadn't filled in quite yet, I wanted to be in the ocean, ready to clock miles by the time that it did. So I made what some might consider a bone-headed decision to try to navigate the flock of commercial traffic that regularly conducts business on NYC waterways, including barges, tugs, the NY Water Taxi, the Seastreak, the Circle Line, Statue of Liberty cruises, and, of course, the Staten Island Ferry, with a tiny outboard and variable breeze. Most of these vessels carry Automatic Identification System (AIS) transponders that provide vessel information including, for example, vessel name and size, speed over ground (SOG), course over ground (COG), and destination. Here's an AIS view of what commercial traffic in New York Harbor looked like at lunch time Thursday afternoon.

The path to the ocean from New York Harbor involves navigating both the Upper Bay and Lower Bay, which are separated by the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

The Upper Bay is marked by the aforementioned commercial traffic as well as massive barges and other ships that are simply anchored in the Bay, often waiting for a pilot. The Lower Bay is marked by the relatively narrow, shoal-lined Ambrose Channel with Staten Island to the west, Sandy Hook to the South, and Coney Island to the east.

My transit from Larchmont, NY to Jersey City, and then to the southern end of the channel in New York's Lower Bay--a distance of about 40 miles--required only 2.5 gallons of gas. Each hour, I would perform 16-20 hand pumps from my jerry can through a fuel line into the 0.25 gallon gas tank built into the outboard, which allowed my engine to push me along at an average of 4 knots when the breeze had completely shut off. The process was slow-going. The lack of speed, however, allowed me to appreciate the City before it eventually faded to a speck of light in the distance.

As I exited Ambrose Channel, and passed by some rather massive container ships, the variable breeze became a consistent 9-11 knot south-southwesterly. I shut off the engine and lifted her out of the water. At about 1630 EDT Thursday afternoon, I was sailing under clear blue skies, and clocking miles towards my goal of qualifying for the 2015 Bermuda 1-2 Yacht Race.

GETTING UNDERWAY OFFSHORE.

After exiting Ambrose Channel and avoiding packs of anchored behemoths, my goal was to hit the northernmost "Separation Zone" that provided a 1.5-3 mile buffer between commercial traffic heading inbound from, and outbound to, Nantucket Shoals.

This target coupled with the consistent south-southwesterly allowed me to jib reach at a true wind angle (TWA) of about 90 degrees. I rigged an outboard lead on my 140% genoa and, under full main, made my way into the ocean at about 7.5 knots of boat speed in breeze that had built to about 10-13 knots.

At around 1830 EDT, with the knowledge that the breeze would be building considerably later in the evening as the forecasted low pressure system moved through, I prepped dinner in Abilyn's gourmet kitchen, which consists of a JetBoil stove mounted to a gimbaled stove manufactured by UK-based Safire Associates.

On the menu was AlpineAire dehydrated pepper beef and rice. Normally I would dine on a sous vide meal prepared by my co-skipper (and master chef), but he was busy making chedda elsewhere in the world. Food prep was quite efficient. The JetBoil boils 16 ounces of water in 2 minutes flat. After 12 minutes of soaking the dehydrated beef and rice in the boiling water, I had a hot meal that I ate out of a GSI Outdoors Fairshare Mug that I picked up from REI at the suggestion of fellow Mini sailor Tony Leigh. The pepper beef and rice tasted...okay. I couldn't complain though. I was offshore having re-hydrated food on a Mini Transat boat with a titanium spork! Pretty cool.

After dinner, I checked the instruments and noticed that the breeze had clocked more to the west, which opened up my sailing angle, and allowed me to set the kite for the first time offshore. Heeding the wisdom that I didn't need to be a hero out there, I opted for the Code 5 and not the much larger, and fuller, Code 2. The kite went up cleanly (as it always does...I'm a bowman at heart) and I was able to keep sailing in Separation Zone and away from any potential commercial traffic while maintaining boat speeds of around 7-9 knots.

As I played with sail trim, I set up the autopilot and locked her into a groove where she maintained course without rounding up with each puff. Being able to trust my autopilot in these conditions allowed me to sit on the cockpit floor, lean my head against the bulkhead, and get a few minutes of rest.

All was well and I was able to send home a preset message using my inReach SE: "I am alive and okay."

The kite stayed up until about 2300 EDT. What prompted me to take it down was when I looked back against the still-bright lights of Coney Island and the Rockaways and noticed a distinct cloud line that paralleled the coast. I knew this was the low, and I knew it would bring bigger breeze from a different direction. I've learned from more than a few accomplished offshore sailors that anticipation is one of the essential skills for racing safely and effectively offshore, and I put this skill into practice Thursday night. I was also approaching a group of fishing boats, and decided that the best thing to do was gybe away. Not wanting to gybe for the first time offshore at night with the kite up, I doused and tried to get away from what was turning out to be rush hour in the ocean.

THE LOW PRESSURE SYSTEM ARRIVES.

PITCH BLACKNESS SETS IN.

Not too long after I had gybed onto port (at around Friday morning at 0150 EDT), the cloud line overtook me. It brought 17 knots of breeze to start and a 90 degree shift from the west to the north, requiring me to fall off dramatically. Since the windspeed jumped nearly 100% in a matter of seconds, I made the conservative decision to put a reef both in the main and the genoa. Reefing the genoa was accomplished from the cockpit. However, in pitch blackness (the moon had not yet risen) and 40 miles from land, I left the security of the cockpit and, led by my tether, moved forward to the bow to tie up the foot of the genoa with sail ties. I could see nothing but blackness ahead of me.

With the boat under control, I took the helm and proceeded to hand steer through the night as the wind rose to around 20 knots and held steady. But, to maintain my reaching angle, I was being pushed farther south than I had intended, and directly towards the Panamanian-flagged Grand Dahlia, a container ship measuring 656 feet long by 106 feet wide (and massively tall) that appeared to be drifting towards New York--her SOG never reached more than 1.3 knots. Yet, I was finely attuned to the possibility that she might pick up her pace at any moment, and not be able to get an echo on me--not that it would matter if she did; it was my responsibility to avoid her. So I tried to stay as far away as possible, first sailing above her as the breeze clocked to the right, and then below her as the breeze oscillated back to the left.

THE SEA STATE CONTINUES TO BUILD.

As I was playing keep-away with boat having a gross tonnage of 59,217 tons, the breeze began to pick up into the low 20s and clocked from the north to the northeast, which again forced me slightly farther south. Other than the lights of the Grand Dahlia, I couldn't see anything in front of me, due in part to the waning crescent moon, which illuminated only 27% of the "moon disc". But I knew that sea state had built considerably since the low pressure arrived earlier in the night as I was now regularly surfing down waves, listening to the keel sing, and hitting boat speeds of above 10 knots, even with just a reefed main and reefed genoa. All the while, I was able to look up to see a crystal clear sky painted with a universe of stars--something you don't normally see in New York City outside of a planetarium. It's both glorious and tragic that there is really no good way on a pitching and rolling boat to capture the night sky in an image to send back home. I took a mental photograph, and filed it away to be accessed some day in the future likely at my desk at work.

But, as much as I just wanted to look up and gaze, I needed to keep the boat moving.

The Grand Dahlia continued to stalk me for hours. Ultimately, I passed her to the southwest at around 0530 EDT Friday morning at a range of about 4.7 miles.

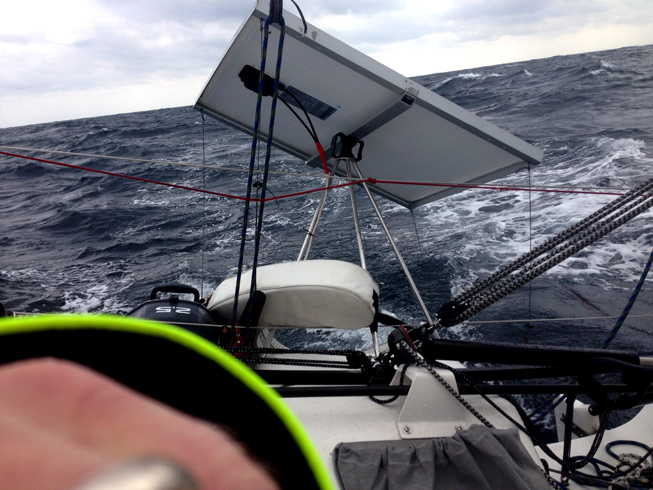

For another hour and a half, I continued along on port tack with my bow pointed towards Santo Domingo some 1,200 miles away. As the sun rose, I began to see what I would be facing for the next 100 miles when I planned to turn the corner and make my way back to New York Harbor: steep, short-period, breaking waves approximately 10 feet tall from trough to crest, moving swiftly from multiple directions including predominantly northeast and east--conditions slightly more challenging for a 21-foot race boat weighing in at around 2,500 pounds than for a larger race boat or heavier passage maker. I went to turn on the GoPro to memorialize the moment, but the cam had run out of juice. This is the only image I was able to snag of that early morning sail.

INTO THE WASHING MACHINE.

At approximately 0700 EDT, I turned the corner, and immediately felt the effect the northeast breeze, which had now built to about 22-23 knots, had on the sea state. In an instant, everything became wet. As I began reaching on starboard tack to maintain a reasonable angle relative to the northeasterly breeze, I wrestled with the waves and green water that began breaking over the side of the boat. Exhaustion set in after an hour. The last time I had more than a few minutes of sleep was at Liberty Landing Marina 19 hours earlier.

I also realized that I needed my Aegir ocean jacket on me immediately. Overnight, I had removed it to keep from overheating as temperatures remained mild and the boat remained dry. Bad move. Now that I was experiencing 20+ knots of much colder air from the northeast, and an increasingly wet boat, I desperately needed that jacket. Waves were breaking over the side of the boat from from the forward quarter, abeam, and aft quarter. As the bow dug into waves, gallons of green water rushed back over the deck into the cockpit. When I tried to hunker down in the cockpit, waves broke over my head. My head and torso were soaked. I could have quickly jumped down below to grab my jacket. But I didn't trust my autopilot to hold a course given the wave state, and seasickness began to set in, all but obliterating any desire to move.

It was 0808 EDT when I communicated home that, yes, I was in a washing machine. I was cold. I was wet. I hadn't slept. I was seasick. I was hungry. I didn't want to move. I wanted out of there.

GETTING FRUSTRATED.

Sailing in this state made me question what I was doing. Why was I out there, by myself, on such a small boat? It didn't make sense to me, as I my mind was overtaken by the burning desire to be at home, on the couch with my 4 1/2 year old girls, watching the Disney movie du jour, or chasing after them as they scootered masterfully down the streets of Brooklyn. Why did I decide to leave my family to go sailing in this shit, and at the same time put my own life in jeopardy, I asked myself. So my ultimate goal changed from qualifying for the Bermuda 1-2, to just getting home, at which point I felt that the original reason for being out there was all but lost.

At 0900 EDT Friday morning, home was over 95 miles away. So I set the autopilot on deck to steer a TWA of about 85-90 degrees, and went down below for some rest. Not more than 5 minutes after I actually passed out down below, the sound of water bashing against the hull stopped, which was an odd feeling. I felt the boat change direction. Shit, the boat was falling off course and the AP wasn't correcting. I leaped up out of my bunk and lunged for the autopilot ram on deck to detach her from the tiller as the boat continued to fall off. But, I was too late. The main snap loaded and the boom swung across the deck, crashing against the heavily tensioned starboard runner. Abilyn had crash gybed. My first concern was the rig, which could have easily been lost. But, when I looked up, my masthead was just where I left it. I quickly tensioned the port runner and eased the starboard runner to free the boom, which flattened out the boat. Once I trimmed the reefed genoa on starboard, I was able to make headway and soon tacked back on course. Although disaster was averted, the continued frustration of not being able to rest continued to hinder my forward progress.

After the incident with the autopilot, I hand steered some more and continued to watch the reading from the masthead anemometer. The breeze had risen to a consistent 26 knots by mid-morning on Friday, so I set a second-reef in the main and switched out the headsail to my storm jib. Putting a second reef in the main was easily accomplished from the cockpit, except that I needed to go forward to attach a ring on the luff of the main with the J-lock on the boom--Abilyn has only single-line reefing. I then went forward to douse and detach the genoa, stuff it below, and then hook up the storm jib. Because of limited practice with the storm jib, I hadn't devised a way to keep the genoa hooked up while engaging the storm jib at the same time given that both sails utilize brass hanks. In de-brief with my co-skipper, he described to me basically stuffing the luff of the genoa as far down the forestay as possible and then hanking on the storm jib overtop the genoa hanks. This will certainly be a focus of more practice in the future.

Once the double-reefed main and storm jib were operational, I grabbed the helm and sent the autopilot to timeout for a few minutes for not having good manners with that whole crash gybe thing. Not too long after, I quickly realized that I was now exponentially more exhausted than before. I couldn't continue without rest, so I trimmed the storm jib on the windward size, eased the main, and set up the boat to lay hove-to.

With the the satisfaction that the bow would lay about 30 degrees to the breeze for as long as I wanted, I went down below for some rest and to change my HH Warm Freeze 1/2 Zip top, which was now saturated with salt water to a point where I was consistently shivering. As I began changing out my gear, I noticed that my only other base layer had fallen into a pool of water. Ughhh...throw me a frickin' bone. My mental fatigue and frustration deepened, which led me to text an alarmingly negative message from my satellite communicator at 0959 EDT Friday morning:

"B 12 off. I am not an ocean sailor. Boat goin up [for] sale when I get back."

Sometimes you're the hammer, and sometimes you're the nail. At this point in the journey, I was the latter. But although I was getting beat up, I needed to get home--and before that, I needed sleep. So I donned by HH Crew Jacket and my Aegir Ocean Jacket (which I should have been wearing since sunset the previous night), crammed a Clif Bar down my gullet, and passed out, but not before checking to see if there were any nearby AIS targets. Clear.

What amounted to 25 minutes of sleep felt like mere seconds. Upon awakening, my mind felt slightly rejuvenated, although my body was still reeling from seasickness. I climbed up on deck, clipped in, freed the backwinded storm jib, and set a northwesterly course for home, and out of the washing machine. Not feeling up to steering (or really doing much of anything), I set the autopilot and trimmed the sails to hold a reach (85-100 degrees TWA), and then hunkered down in the cockpit to try to let my body recover.

PROGRESS. REASSURANCE.

Surprisingly, the autopilot performed magnificently as I reached along at 7.5-8 knots under double-reefed main and storm jib. The breeze continued to build and maxed out at 28 knots, although Abilyn never became overloaded. The waves continued to crash over the deck, but my Aegir ocean kit kept me dry.

For the next 6 hours, I sailed with this configuration, adjusting my course as the breeze clocked from the northeast to north-northeast. During the afternoon, I made considerable progress--not only in terms of miles covered, but also in terms of bodily recovery. The seasickness began to subside despite the sea state being at its worst. Nearly every wave was a breaker. And, more than once, I was hit by a wave that came directly from abeam and lifted Abilyn up and pushed her sideways and over as the wave broke on top of us. Yet, she (and the autopilot) never faltered. As the day went on, I became more and more reassured that Abilyn, indeed, was an oceangoing boat. In August 2013, when I competed in the Stamford Yacht Club Vineyard Race, I got a glimpse of Abilyn's strength as we battled upwind in 22 knots of breeze off Block Island. But I was now in the open ocean, conditions were much more severe, and I was much farther away from assistance.

Later in the afternoon, as the breeze abated to 17-22 knots, and I felt a resurgence of energy, it was time to make my final push towards home.

HOMEWARD BOUND.

Even as my mental state improved, I never wavered from my decision to "put the horse in the barn" as soon as I returned to New York Harbor rather than turning around and staying offshore for another day and a half to meet the durational requirement specified in the Bermuda 1-2 NOR. The ocean introduced itself to Abilyn, and me as a solo sailor, and we were happy to say, "Nice to meet ya. But, peace out for now."

At around 1700 EDT Friday afternoon, I shook out both reefs, and sailed deeper as the breeze had clocked more to the east. I sailed for about 15 minutes before deciding that I had enough energy and mental acuity to go up with the kite. Out came the Code 5 again.

Once the kite filled, I was carving waves like Kelly Slater, riding up to about 115 degrees TWA to catch the wave, and the dropping down to about 130-135 degrees TWA to surf--all the while staying within the Hudson Canyon Separation Zone. The Grand Dahlia was nowhere to be found!

I contemplated taking the kite down when the breeze rose to a sustained 22 knots. But, the rudder was never overloaded as the main was well eased, and taking the kite down would have meant wiping the grin from my face as the speedo regularly showed 12-13 knots. Plus, with the kite up, I knew it wouldn't be long before I was back in New York Harbor, which was now my ultimate goal.

By sunset, commercial traffic picked up considerably as I closed in on Ambrose. So I doused the kite and ended my sleigh ride. The video below gives a brief glimpse of that sleigh ride, but by no means does it justice.

By 2230 EDT Friday night, I was back in Ambrose Channel, now only a few hours from a decent night's rest.

RETURNING TO THE BRIGHT LIGHTS OF NEW YORK.

Entering the channel, I still had a considerable distance to cover before I could tie up in Jersey City--about 14 nm. And now, the breeze was directly astern and hovering around 9 knots. The relatively light air made for a tough transit because the sea state was still kicked up. I did my best to gybe back and forth up Ambrose channel and avoid the usual suspects. I had one or two vessels tag me with spotlights, which would have hurt my night vision except for the fact that the bright lights of Coney Island had already done just that.

Soon enough though, I had reached the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, and the breeze had picked up once again to 17-20 knots from the southeast, which actually allowed me to plane a little bit as I sailed into the Upper Bay.

I grabbed the rest of the sandwiches my wife had prepared, and, along with some coffee, had a nice meal that restored a sense of home to my body, and to my mind.

But that didn't help me from experiencing some rather interesting visions as the bright lights of New York City played tricks on me. I could have sworn that, right in the middle of the harbor, somebody was constructing a giant, illuminated T-Rex art installation. Okay, I needed to get to my slip...immediately.

At 0113 EDT Saturday morning, Abilyn and I were at rest.

FINAL THOUGHTS.

After I read through my synopsis, I had to remind myself that I spent only 29 hours offshore--even though I spent a total of 78 hours on the water to be able to get that 29 hours (and over 200 miles) of offshore sailing. Irrespective of how long I was out there, it was still extreme for me. 28 knots of breeze and tall, steep, breaking seas might be within the comfort zone of some. But, until this experience, I would not have characterized my comfort zone as being comprised of those elements. Moreover, the fact that this was my first time sailing single-handed offshore served to amplify the magnitude of each moment, both positive and negative. At the very least, I pushed my limits. I have a new comfort zone. And, more importantly, I'm able to reflect on this experience so that it propels me forward to the next limit, and a new comfort zone. I recognize what I did right (including returning home when I did), what I did wrong, and what I can do to improve. For all these reasons, absolutely nothing about this adventure can be considered a failure.

After a decent night's rest at Liberty Landing, I returned to the boat the following night to deliver her back to Larchmont with the assistance of a work colleague. Given the tides, we left Liberty Landing Marina at 0100 EDT Sunday morning, and hit Hell Gate at slack tide. After hooking back up to our mooring at about 0630 EDT, we had a couple of Brooklyn Lagers for breakfast, and to celebrate--not just the offshore aspect of the adventure, but also (1) a successful boarding and safety inspection by the United States Coast Guard on the delivery back to Larchmont, and (2) a successful transit past the United Nations the same night, which included a USCG escort for about 20 city blocks since the General Assembly was in town. The rifleman manning the M240 machine gun was a nice touch.

Going forward, I'm not ready to give up on my goal of competing in the 2015 Bermuda 1-2 Yacht Race, and not ready to sell the boat just yet. I have one more opportunity this season to sail offshore, and likely only one additional opportunity next spring before the big race. These opportunities will only benefit me as I move forward to June 2015. After that, who knows.

See you out on the water.

SYNOPSIS.

Stats:

Total distance covered (mooring to mooring): 273.28 nm

Total elapsed time: 3 days 6 hours 8 minutes (78 hours 8 minutes)

Total offshore distance covered: 204.45 nm

Total elapsed time offshore: 1 day 5 hours 41 minutes (29 hours 41 minutes)

Top boat speed: 12.1 knots SOG (to be confirmed)

Top observed wind speed: 28 knots (northeasterly)

Average wave height during toughest conditions: 4.5-5 feet (9-10 feet from trough to crest)

Best 24-hour offshore distance: 175.66 nm (7.3 kts avg.)

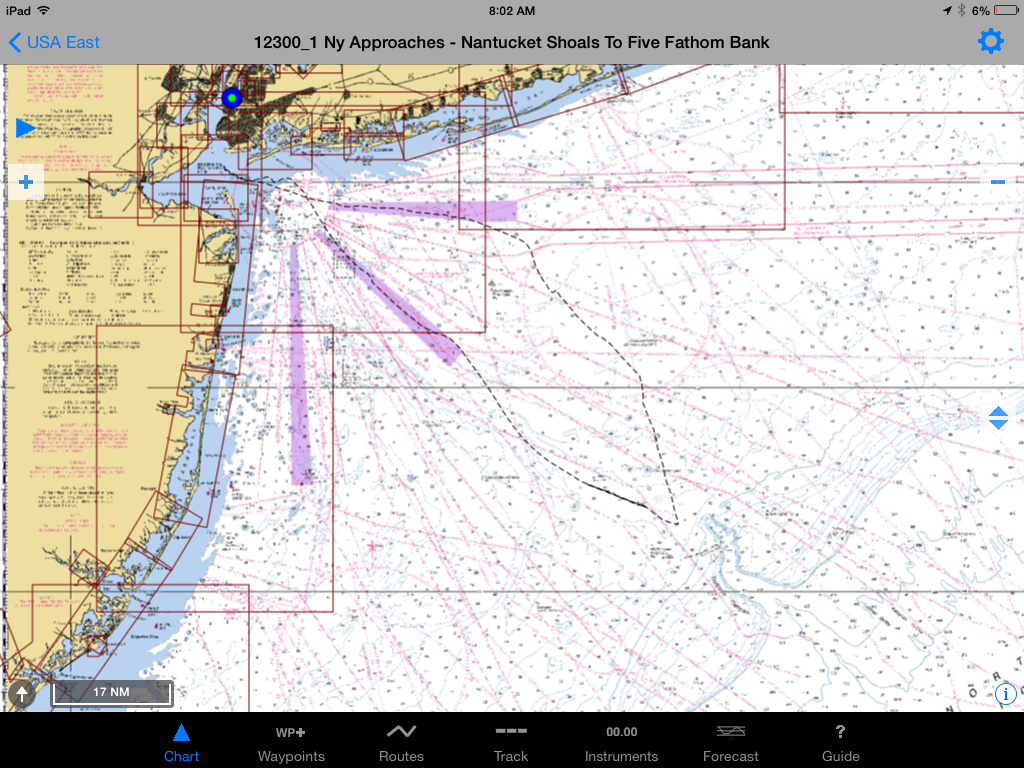

Track:

Below is my offshore track from the Lower Bay into the ocean. The track also shows how close I came to reaching Hudson Canyon proper and the edge of the continental shelf, which might have provided some relief from the short-period, steep waves kicked up on the shelf by the northeasterly and easterly breeze.

What I did right:

- Adequately planned the route so that Abilyn would not need to beat--a point of sail that she and other Mini Transat boats try to avoid.

- Anticipated changes in wind strength and direction based on daily weather analysis leading up to the time of departure.

- Planned transits to and from Larchmont, NY, and New York Harbor by adhering to tides and currents.

- Packed sufficient food and water to account for 2+ days of offshore sailing.

- Sailed conservatively with the wisdom imparted from a good friend that I did not need to be hero. During the first night, I doused the kite well before the anticipated wind shift and increase in pressure. I reefed the genoa early at 17 knots under reaching conditions. I put a second reef in the main and switched to a storm jib early enough so as to not be overpowered when the pressure maxed out at 28 knots. I also did not shake out the reefs until after the breeze abated to a consistent 15-20 knots.

- Recognized when I absolutely needed to sleep, and did what was necessary to rest, which at one point meant heaving-to.

- Remained clipped in while on deck, at all hours of the day.

- Kept my head both inside the boat monitoring AIS targets and outside the boat to monitor potential traffic without AIS transponders, and remaining vigilant to keep clear of all traffic, including by sailing in the Separation Zone, not in the shipping channel.

- Communicated regularly with my family to let them know I was alive and okay.

What I did wrong:

- Did not do a good job of taking care of myself. Sleep - leading up to this journey, my sleep was sporadic and irregular. I slept for 3 hours Wednesday night before delivering Abilyn to Jersey City. 10 hours later, I caught 2 hours of additional sleep at the dock at Liberty Landing Marina. Then, during the entire 29 hours I was offshore, I might have slept only for about 30 minutes. Food - I needed to eat more regularly, and needed to consume more calories. The only "meal" I had during the 29-hour offshore was at the start of the voyage--and that consisted of a 680 calorie pouch of dehydrated food. The only other food I ate offshore included Clif Bars, Clif Shots, and some chocolates. Water - As with food, I needed to drink more, and more regularly. This was apparent when my urine color was more amber than clear. Gear - I let myself get wet, and cold. I was then forced to focus on staying warm, instead of sailing the boat. My full ocean sailing kit needed to stay on at all times while on deck.

- Did not appreciate the sea state on the continental shelf that would accompany the 25 knots of northeasterly and easterly breeze.

- Did not bring my scopolamine transdermal patch, which I bring on ALL my offshores.

- Did not set short-term goals, which would have helped me remain positive, and would have kept my mind active as conditions deteriorated.

What I learned:

- Although I knew this theoretically, I now have the experience to say it: solo offshore sailing is f**king tough. The physical aspects of sailing solo are one thing, but the mental aspect of sailing alone in the open ocean is another thing entirely.

- Abilyn is tough, and is, indeed, an oceangoing boat.

- I should have looked after myself better. I am extremely detail oriented and should have had a list in the cockpit of each task I needed to complete at regular intervals. This would have kept me busy, thus preventing my mind from wandering to more negative thoughts. I needed to focus more on sleep, food, water, and keeping my body in tact.

- I should have worn my offshore jacket AT ALL TIMES, and did what I needed to do to regulate body heat WITH MY JACKET ON.

- Before the low pressure system arrived Thursday night, I should have pre-made meals so that no cooking was necessary when conditions were at their worst. Thanks to co-skipper, Sam Cox, for that tip.

- I should have packed a spare set of base layers sealed in a plastic bag in case of emergency, such as when I went down below to change layers and found my second pair in a pool of water.

- I should have practiced more with the storm jib. Fully removing the genoa before hanking on the storm jib was risky. I could have lost both sails overboard.